It seemed like I had been wanting to go to India my entire life. That wasn’t strictly true of course but, as the years cycled by, it came more and more to seem that way. Even after we started to travel more, India wasn’t working for us. The reason? My husband and I were both teachers. The only months of the year when we had enough time for the sort of trip we felt India deserved were mid-June to mid-September. Those months pretty much coincided with India’s monsoon season so travel to India was definitely a non-starter.

When we retired, each of us picked a place we wanted to travel to that hadn’t been possible before because of our schedule. No surprise here—I picked India. First, we signed up for a birding tour (a favorite hobby for me and a passion for Vernon) and then we arranged for a private tour that he referred to as “Mammals and Monuments”; of course, my focus in the “mammal” part was seeing tigers. At least one tiger. Accordingly, our tour included visiting five different national parks/tiger reserves—Panna, Bandhavgarh, Kanha, Pench, and Satpura. The birding tour would go to Ranthambhore and Corbett, so altogether we would be in seven well-known tiger areas. Surely, we could manage to see a tiger in at least one of these spots.

My preparations for India included putting all of Kipling’s works on my Kindle. A colleague mentioned Jim Corbett and I read his masterpiece, Man-eaters of Kumaon. But I also read John Valliant’s much more recent The Tiger: A True Story of Vengeance and Survival. The story of a Siberian tiger who retaliates when a man steals from him was a real eye-opener—and not just because the book also included background on local culture, politics (both local and international), ecological concerns and the balance between living at near-starvation levels and being able to handily survive (perhaps for years) by killing a tiger.

Valliant repeatedly made the point that tigers and men are similar—both remember, analyze, organize and retaliate when a situation calls for action. One of Valliant’s sources, referring to the tiger, said, “Him all same man, only different shirt”; in other words, we and animals are all brothers and sisters under the skin.

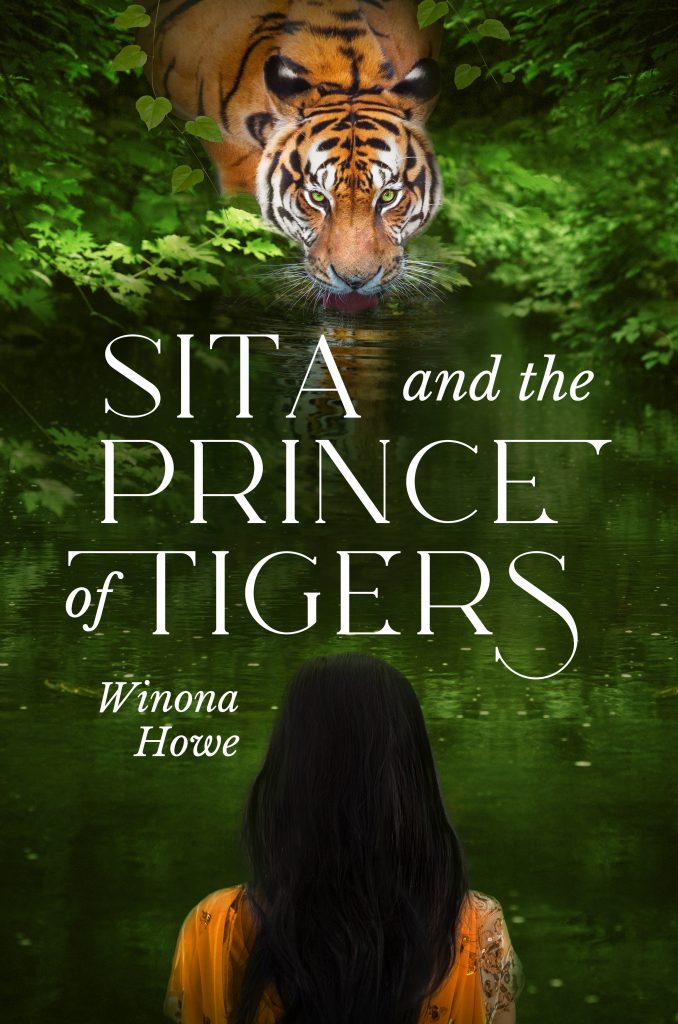

It finally happened in Bandhavgarh. We’d taken game rides day after day, straining our eyes in every direction, even though we knew we could not possibly spot one before our experienced, sharp-eyed guides. And when I saw my first wild tiger, it was surprising just how different the experience was from seeing a tiger held captive in a zoo with a moat and fence between us. Lying several yards from the road, the young female was all that a tiger should be: beautiful, regal, graceful, and powerful.

But she was also curious. She radiated curiosity as her eyes wandered over the people who were watching her. She seemed to be questioning our intent in seeking her out—wondering about us, just as we were wondering about her. Then someone whistled, and suddenly she was standing, although the movement was so fast no one actually saw her get to her feet. Then she simply walked away into the jungle and was gone. She’d seen enough of humans, but I knew I’d not seen enough of tigers. I simply had to see more.